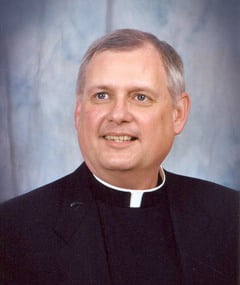

When the Diocese of Lafayette released its list of accused priests last week, 11 of the 37 members of clergy had never been publicly accused. Among them is the Rev. John de Leeuw, who made arrangements to defend himself in death.

Shortly after publishing the church’s list, KATC was contacted by a friend of de Leeuw, who shared with us more than 100 pages of documents the late priest kept about his case. The documents feature his personnel file, correspondence from the diocese, and notes about the accusations his friend says were handwritten by de Leeuw.

The documents provide de Leeuw’s side of the story, but they also show how the diocese was concerned about “scandal” and tried to minimize publicity on cases of clergy sex abuse as recently as 2013.

The accusations

In 2011, more than 20 years after his retirement, de Leeuw was removed from active ministry by the diocese following accusations of sexual abuse involving minors. His removal was only made public last week, when the diocese released its list of credibly accused clergy.

In January, concerned about diminishing transparency and openness from the diocese, KATC published its own list of accused priests. De Leeuw was not on our list because up until now, there was no public record of a complaint. Concerned about his absence from our list, Nancy Mouton reached out to tell her family’s story.

“Father John de Leeuw, past pastor of St. Leo the Great, sexually abused me and most of my six siblings in our home for many years,” said Mouton. “He was a regular visitor and dinner guest at our home. It was a very large home where the abuse went undetected.”

Documents provided by de Leeuw’s friend indicate one of Mouton’s older sisters, who is now deceased, was his initial accuser.

“For years Fr. John roamed and groped and grabbed and unbuttoned buttons of our clothing while my dear unsuspecting mother was in the kitchen preparing a feast in his honor,” said Mouton. “Little did she know he had his feast far from the kitchen. He had unlimited access to all of us.”

The church records obtained by KATC show the diocese was aware of accusations against de Leeuw as early as 2009, when Mouton’s older sister was referred to a clinical social worker by the diocese.

De Leeuw had a copy of the social worker’s initial report. The social worker wrote: “She reports him kissing her with ‘an open mouth’ and fondling her on a regular basis. The molestation began at age 13 and continued until she got married.”

De Leeuw apparently wrote “full of false accusations” at the top of the report, and “lie” several times in the margins.

In 2011, several of the siblings took their accusations to the diocese. Mouton says she and her siblings spoke to Msgr. Robie Robichaux, who himself is now accused of sexual abuse involving children.

“In 2011 when we gave our depositions to Msgr. Robichaux, we had hopes for justice, and even monetary compensation for our pain and suffering,” Mouton said. “Robichaux told us we would have justice. He lied.”

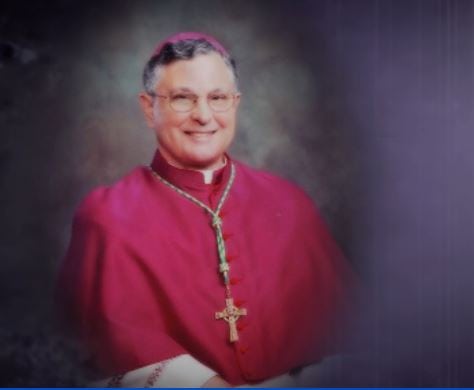

De Leeuw’s own files show that in March 2011, former Bishop Michael Jarrell placed restrictions on his ministry and tried to avoid a scandal.

“In response to the pastoral needs of the Diocese of Lafayette and to lessen any scandal, which may be associated with certain alleged actions of the Reverend John de Leeuw that have been under canonical investigation, it is necessary to issue certain restrictions on his ministry as a priest of the Diocese of Lafayette,” Jarrell wrote to de Leeuw.

The orders from the bishop show that deLeeuw was not to engage in any public ministry, but was allowed to “offer Mass privately in his home without a congregation.” He was also allowed to administer the Sacrament of Reconciliation at his home. He was advised to have no contact with his accusers.

Jarrell also consulted with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Rome. In October 2011, church records show the CDF confirmed the disciplinary measures proposed by Jarrell: “Reverend deLeeuw is not allowed to exercise priestly ministry. He will lead a life of prayer and penance…”

There is no record the diocese ever reported de Leeuw to law enforcement, though KATC still has pending public records requests.

De Leeuw’s defense

The documents provided to KATC by de Leeuw’s friend show the priest maintained his innocence up until his death in 2015 at the age of 97. Even his obituary from that year states: “The last years were very painful for Father John being falsely accused and suffering of kidney failure.”

De Leeuw left his files with his family friend, and instructed him to use his best judgement if the accusations ever surfaced.

Among his files, an undated letter from the initial accuser to Jarrell. De Leeuw underlined phrases including: “I will entertain a substantial offer.” In the margins, de Leeuw wrote “pay a lot and I will stop.”

In a letter addressed “Dear Bishop” and dated “Good Friday 2013,” de Leeuw compared his case to Jesus being falsely accused on Good Friday.

“I am having my own Good Friday,” he wrote. “For nearly two-and-a-half years, although innocent, I have been falsely accused, made to suffer, being condemned and punished, robbed of any priesthood.

“For years now, the Church has been suffering from the consequences of clerical child abuse. Certain bishops shielded guilty priests to avoid scandal.”

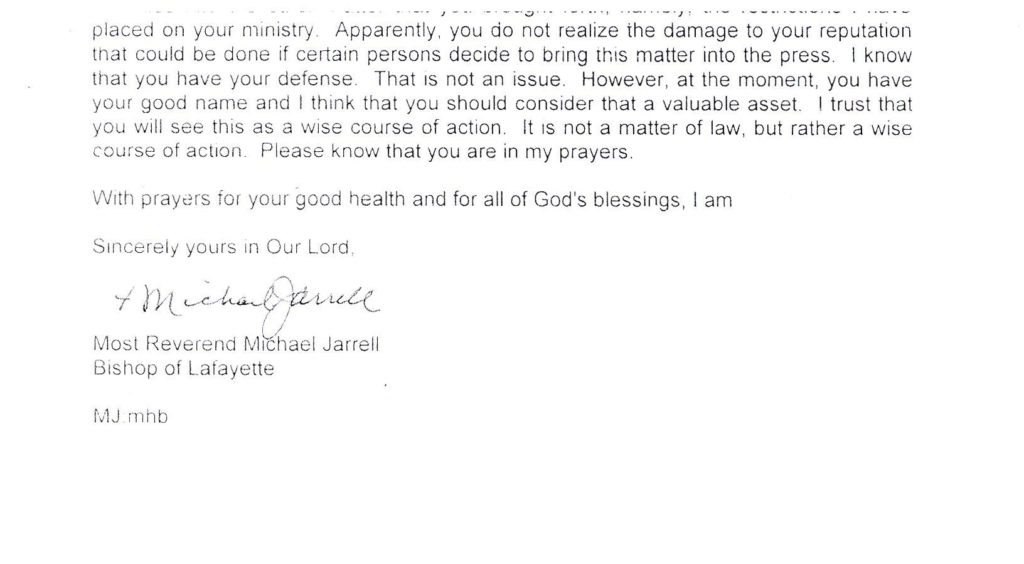

It’s unclear if the letter was ever sent to the diocese, but de Leeuw’s files do have a letter from Bishop Jarrell dated May 20, 2013.

“I have great sympathy for you in the situation in which you find yourself as a result of the accusations brought against you,” Jarrell wrote to de Leeuw. Jarrell then informed him that restrictions on his public ministry remained in effect and could not be modified.

“As bishop, I try to keep in mind the welfare of all priests, especially those who are retired after many years of service. Please be assured of my personal concern for you despite the unfortunate cross that has come into our life.”

Among de Leeuw’s files was a letter to friends who had requested that he baptize their baby.

In the letter, he told them he couldn’t do it because he was “falsely accused.” He says his canon lawyers agreed with him that the accusations were false and that he was “totally innocent.”

However, there is no written record from the diocese to that effect.

In that same letter, de Leeuw questioned how his case was handled by the diocese, writing: “…my bishop sides with the woman out of fear that if she goes public it will bring scandal on the diocese. Therefore he punishes me by depriving me of all priestly ministry outside my house, and that includes baptisms. This is a terrible injustice, but I will have to live with it.”

Accuser plans to file suit

Nancy Mouton says recounting the alleged abuse by de Leeuw still makes her sick to her stomach.

“If you pick up anger in this letter that I’m writing, you are not mistaken,” she wrote in a statement to KATC. “I am beyond angry. I am burning up with rage. I feel the colors of the fire surrounding me, red and blue, yellow and white, scorching thoughts that I still carry in my head about the abuse that continuously took place in my home.”

She says de Leeuw wasn’t the only priest who abused her and other members of her family. She provided KATC with the name of at least one other member of clergy, who is not listed as credibly accused by the diocese and was not on KATC’s list.

Mouton is now planning to file a lawsuit against the Diocese of Lafayette.

Case brings more questions for Bishop Michael Jarrell

As recently as 2014, Jarrell said he saw “no purpose” in releasing the names of accused priests. Private correspondence in de Leeuw’s files show Jarrell was concerned about accusations against de Leeuw going public and bringing about a scandal for the diocese.

“Apparently, you do not realize the damage to your reputation that could be done if certain persons decide to bring this matter into the press,” Jarrell wrote to de Leeuw in an excerpt of an undated letter found in de Leeuw’s files.

De Leeuw’s case is one of at least four under Jarrell’s tenure, where the diocese was made aware of complaints against living members of clergy, but the public was notified, and it was unclear if law enforcement was alerted.

Jarrell was installed as Lafayette’s Bishop in December 2002. Here are the other Lafayette cases:

Smit, who was removed from ministry in 2011, was the subject of complaints by victims as early as 1982. In 2010, a former altar boy came to Jarrell claiming Smit had sexually abused him in the 1970s in Cankton at St. John Berchman’s Church. Smit denied the allegations in writing from Delaware. In 2011, Jarrell tells the Diocese of Lake Charles that the investigation into sexual abuse bore “at least the semblance of truth necessary to proceed according to the norm of canon law.”

In 2003, a woman filed a lawsuit against the Diocese and Larriviere, accusing him of raping her when she was seven years old. The rape occurred during the 1960s at St. Mary Magdalen Church in Abbeville, the suit claimed. The lawsuit was settled in 2008, and Larriviere died in 2014.

Robichaux was removed from ministry last fall, when his accuser came forward with allegations for the third time in a 24-year period. KATC uncovered he was kept in ministry despite allegations in 1994 and 2004. Jarrell and other church officials decided that, since the victim was 16 at the time of the alleged abuse, she was an adult under church law. At a news conference announcing Robichaux’s removal, Deshotel ignored questions from the media if Jarrell’s handling of the case was appropriate. Questions submitted by email have gone unanswered.

A fourth case was reported during Jarrell’s tenure as bishop of the Houma-Thibodaux Diocese, where he served from 1993 until 2002, when he was installed in Lafayette:

Melancon died in prison after being convicted of raping an altar boy in 1996. One of Melancon’s victims was paid $30,000 in 1993 by the diocese, and Jarrell allowed Melancon back to work after he received counseling. The Times-Picayune said the claim was described as “improper sexual behavior or sexual harassment” over 11 years, from 1973 to 1984. Prior to Melancon’s trial, prosecutors asked that Jarrell be held in contempt of court for refusing to answer questions during a deposition in the case. One question involved whether Jarrell knew of any church investigation into sexual misconduct by its clergy, the Associated Press reported at the time.

KATC has reached out to the Diocese of Lafayette for comment, but have yet to receive a response.